Who owns Substack?

The only platform not owned by billionaires? Really? You sure about that?

I see, over and over, this rallying cry on Substack:

“The only platform not owned by billionaires.”

I get the idea. With Trump running around like Hitler, and with the media enabling his every move, people are scrambling for an outlet of information that isn’t entirely in the tank for new regime.

There were a couple of ideas, however, that came to mind.

Not owned by billionaires…

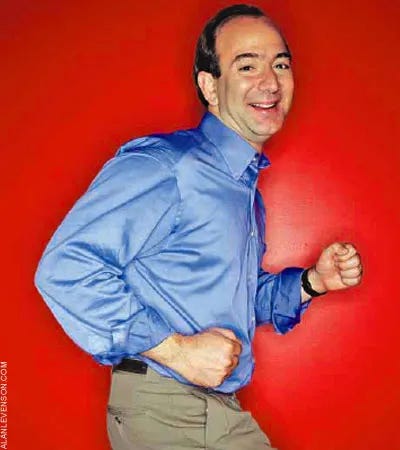

Facebook, TikTok, Twitter (back before it became the gathering ground for the Hitler Youth brigade), Instagram, and others, there was a time when they weren’t owned by “billionaires,” either. There was a time when Amazon, for example, was owned by this clown:

I pulled that picture from a Bloomberg article from 1994. Yeah. By the way, Bloomberg also wasn’t a katrillionaire back then - that also all came later.

Now, of course, Jeff Bezos looks like a freaking Bond villain who launches “dick rockets” into space:

Whatever.

My point is that none of these guys were billionaires at one point. So, saying, “Billionaires don’t own Substack,” isn’t exactly the best proof that somehow everything is roses and sunshine.

Yeah, neither was Facebook. And for what it’s worth, Zuckerberg still looks like a dork, even after all the billions.

Mark Zuckerberg telling everyone that, basically, “facts” can just fuck the hell off at Facebook. We don’t care about facts at all anymore on Facebook. Which is why I’m announcing I kill baby elephants and eat their brains. Well, maybe not - who knows - facts don’t matter.

(Well maybe that’s a bit much, but you get the idea.)

By the way, that’s like a million-dollar watch the guy is wearing. I only know this because I’m a complete watch guy myself. It’s made by Gruebel Forsey - they’re an amazing watch company. But, I digress.

So saying billionaires do not own it isn’t like a guarantee of any kind. And what’s worse, eventually, they’re all owned by billionaires - it’s all a question of timing.

The Social Media Paradox: How Startups Become Empires

Every social media platform starts with a simple promise. Facebook wanted to connect college students. Twitter aimed to make status updates instant and conversational. Instagram focused on sharing beautiful photos. YouTube made it easier to upload and share videos. TikTok encouraged creative expression through short-form clips.

At first, these were just ideas—small, scrappy ventures built by idealistic founders who claimed to care about users, creativity, and connection. The platforms weren’t polished, they weren’t profit-driven, and in many cases, they weren’t even sure what they would become.

But then, it happened. The tipping point.

Once a platform hits a critical mass of users, everything changes.

The Tipping Point: Growth at All Costs

The moment a social media platform reaches mainstream adoption, the stakes shift. No longer just a cool tool for early adopters, the platform has become a full-fledged business. Investors start demanding returns. Advertisers see a goldmine of attention. And the pressure builds—not just to grow, but to dominate.

What was once a company built on innovation suddenly pivots to a strategy of growth at all costs:

Facebook (Meta) went from a social network to an advertising behemoth, squeezing every ounce of data from users to sell hyper-targeted ads.

Twitter, once an open forum for free speech, became a battleground for political manipulation, algorithmic outrage, and content moderation chaos.

Instagram, originally about creative expression, morphed into a dopamine-fueled machine that maximizes engagement, vanity metrics, and influencer culture.

YouTube, once a home for quirky videos and creators, evolved into a monetization battlefield, where algorithms push whatever keeps people watching the longest.

TikTok, the latest in the cycle, is now in the same phase—shifting from a fun app for Gen Z to a hyper-optimized engagement engine, powered by data-hungry AI.

Each platform, at some point, made a choice: prioritize users or prioritize profit. And every single one chose profit.

The Greed Phase: Consolidation, Control, and Power

Once social media platforms reach monopoly status, the final stage begins—consolidation of power. These companies no longer innovate as much as they buy out innovation.

Meta (formerly Facebook) absorbed Instagram and WhatsApp, eliminating competition and ensuring dominance in social networking and messaging.

Alphabet (Google’s parent company) took over YouTube, integrating it into its vast advertising empire.

Twitter, under Elon Musk, is now a playground for personal control, erratic policy changes, and monetization experiments.

TikTok, owned by ByteDance, is a global powerhouse, leveraging user data and algorithmic addiction to drive engagement and revenue.

At this stage, the platforms stop being just “tech companies” and become something bigger: media empires that dictate the flow of information, attention, and even reality itself.

They control what news people see.

They determine what content gets engagement.

They shape political narratives.

They decide what voices get amplified or silenced.

And yet, the original founders—the ones who started with grand ideals—are either gone, sidelined, or fully absorbed into the machine.

Mark Zuckerberg, once an awkward college kid, is now the architect of one of the most powerful surveillance and advertising networks in history.

Jack Dorsey, the free-spirited Twitter co-founder, was pushed out and later watched his company spiral under new ownership.

The founders of Instagram? They left after Facebook turned their platform into an engagement-obsessed clone factory.

The YouTube creators? Pushed aside by algorithmic trends that favor corporate media and endless watch time.

The Cycle Will Repeat

This is the paradox of social media. Every platform starts with a mission. Every platform ends with a monopoly.

The cycle keeps repeating because these platforms are not just businesses anymore—they are infrastructure. They are more powerful than traditional media, more influential than governments, and more entrenched in daily life than most people realize.

The next “new social platform” will start small, promising something fresh.

It will gain early adopters, attract attention, and grow.

It will hit its tipping point, get flooded with investors and advertisers.

The mission will shift from users to revenue.

It will consolidate power, absorb competition, and become another empire.

And the cycle will begin again.

The only real question is: What’s next?

Because we already know how it ends. With that - let’s look at “Substack.”

The Story of Substack: A New Publishing Revolution

In 2017, three entrepreneurs—Chris Best, Hamish McKenzie, and Jairaj Sethi—came together with a vision to change the way writers publish and get paid for their work. They saw a problem: traditional media was crumbling under the weight of ad-driven revenue models, and social media platforms were prioritizing engagement metrics over quality content. Writers were left scrambling for attention, often forced to churn out content that fit the demands of algorithms rather than their audiences.

The trio believed there was a better way. They wanted to create a platform where writers could publish directly to their readers, free from the constraints of advertising, editorial interference, or social media gimmicks. More importantly, they wanted these writers to be able to make a living from their work. The solution? Substack, a simple subscription-based newsletter platform.

At its core, Substack offered something deceptively simple: an easy-to-use platform for writers to launch their own paid newsletters. The company handled the technical heavy lifting—email distribution, payment processing, and design—so writers could focus on what they did best: writing. In return, Substack would take a small percentage of the revenue.

The timing was perfect. Traditional media outlets were laying off journalists in droves, and social media platforms became increasingly toxic for nuanced discussions. Writers, journalists, and thinkers were looking for a new home—one where they could own their audience, control their revenue, and escape the influence of advertisers and editors. Substack provided that refuge.

Early adopters like journalist Casey Newton, historian Heather Cox Richardson, and culture writer Anne Helen Petersen proved the model could work. Many writers who had spent years navigating the precarious world of freelance journalism suddenly found themselves making six-figure incomes directly from their readers. It was a publishing revolution—one where power shifted from institutions to individuals.

But success brought challenges. As Substack grew, it found itself at the center of debates over content moderation, platform responsibility, and the ethics of digital publishing. Unlike traditional media companies, Substack positioned itself as a neutral platform, allowing writers to publish what they wanted without editorial oversight. This hands-off approach attracted criticism when controversial figures used Substack to spread misinformation or divisive opinions. The company resisted calls to take a stronger stance, arguing that its mission was to empower independent writers rather than act as a gatekeeper.

Meanwhile, competitors emerged. Platforms like Ghost, Beehiiv, and even Twitter (with its paid subscription feature) sought to capture a piece of the newsletter boom. Yet Substack retained a strong hold on the market, largely because of its first-mover advantage and its writer-friendly ethos.

As of today, Substack remains privately owned, with its original founders still steering the ship. The company has secured funding from major venture capital firms, including Andreessen Horowitz and Y Combinator, allowing it to expand its offerings. Audio features, community tools, and even video capabilities have been introduced, turning Substack into more than just a newsletter service—it’s a full-fledged media ecosystem.

The question now is whether Substack can maintain its independence and its commitment to writers in a landscape increasingly dominated by big tech and shifting media trends. Will it eventually go public? Will it succumb to the pressures of investors demanding higher returns? Or will it stay true to its original vision of putting power back into the hands of writers?

The Inevitable Fate of Substack

Every tech platform starts with a dream. Facebook wanted to connect the world. Twitter aimed to give everyone a voice. YouTube sought to make video-sharing easy. At first, these were small, scrappy ventures, championed by idealistic founders who swore they were different. They weren’t about profit; they were about empowering people.

Substack is in that phase right now.

It promises independence, a direct connection between writers and readers, and a refuge from the algorithm-driven chaos of social media. It has positioned itself as the anti-corporate alternative to traditional publishing, a place where writers own their audience, control their revenue, and escape the editorial interference of big media. And for now, that’s true.

But if history has taught us anything, no platform stays pure forever.

The Tipping Point: When Growth Becomes the Priority

Right now, Substack is thriving on a simple, writer-friendly model: take 10% of subscriptions, let writers control their content, and don’t mess with their audiences. But at some point, that won’t be enough. The investors—Andreessen Horowitz, Y Combinator, and other venture capitalists—aren’t in this for charity. They want returns.

And returns mean growth.

Here’s how it will happen:

The Revenue Squeeze Begins – Substack’s 10% cut might start creeping up. Maybe it’s an extra fee for premium placement in discovery. Maybe they introduce platform-wide ads, cutting writers in just enough to keep them from leaving. Slowly but surely, monetization shifts from empowering writers to extracting more value from them.

The Algorithm Arrives—Right now, Substack’s power lies in its simplicity: Writers succeed based on their ability to attract and retain subscribers. But that’s not how big platforms make real money. The next phase will introduce subtle algorithmic “optimizations”—perhaps to help readers discover new writers, but really to prioritize content that drives engagement, clicks, and growth.

Content Moderation Wars Begin – As Substack grows, so will the controversies. Which writers are allowed on the platform? Which ones are considered too dangerous, too controversial, too problematic? Right now, Substack prides itself on free expression, but that won’t last forever. Governments will pressure it. Advocacy groups will demand action. Payment processors may threaten to cut ties. At some point, Substack will have to choose between being a neutral platform and maintaining its business. It will pick business.

Big Media Moves In – The biggest threat to Substack’s indie ethos isn’t government regulation—it’s traditional media. Right now, it’s a refuge for independent writers, but as the platform grows, corporate media will take notice. Some will try to replicate it. Others will push for deeper integration. A few will demand that Substack prioritize their brands over solo writers. Over time, what was once a writer-first ecosystem will start looking a lot like the media landscape it was supposed to disrupt.

The Next Big Competitor Emerges – Every dominant platform creates the conditions for its own downfall. When Substack inevitably drifts toward a more centralized, monetized, and controlled version of itself, a new competitor will rise—perhaps a decentralized publishing network, perhaps an alternative built on blockchain technology, perhaps something we haven’t imagined yet. It will market itself exactly as Substack once did: as the indie alternative to the now-bloated media empire. And the cycle will begin again.

The Inevitable Fall

Substack won’t collapse overnight. These things happen gradually, with small, almost imperceptible changes.

A tweak to the revenue model here.

A new content guideline there.

A few big partnerships that shift the balance of power.

At first, the writers won’t even notice. Then one day, they’ll wake up and realize that Substack is no longer the indie-friendly paradise it once was. The power has shifted. The best opportunities go to the most profitable creators. The platform favors content that serves its business model, not its users.

By then, the original founders will either be gone, sidelined, or fully absorbed into the machine. The company that once swore it was different will have become just another media empire, fighting for attention, engagement, and dominance.

It’s not a matter of if—it’s a matter of when. Because in the end, every platform follows the same path.

The Unavoidable Endgame: What Comes Next?

Substack is, for now, a writer’s paradise. No algorithms messing with visibility, no corporate overlords dictating editorial slants, and no reliance on advertisers who pull the strings. It’s direct, it’s simple, and it works—for now. But history tells us that nothing stays pure forever.

The moment the numbers stop climbing at a breakneck pace, the pressure will mount. First, it will be subtle—higher fees, small algorithmic tweaks in the name of "discovery," a push toward incentivizing only the most profitable writers. Then, as the VC money demands bigger returns, the changes will accelerate. Writers will realize they are no longer truly independent and that their work is being shaped by unseen forces pushing engagement, virality, and revenue over substance.

And then? The exodus will begin. The smartest, most forward-thinking writers will see the writing on the wall and look for the next haven. Maybe it will be a decentralized network or a new platform promising that this time, it’s different. And for a while, it will be.

But the cycle is inevitable. Every platform that starts with a noble purpose eventually finds itself caught in the gravitational pull of power, consolidation, and greed. The founders will either sell, be sidelined, or compromise in ways they once swore they never would.

So what does this mean for you, the writer? It means the time is now. If you’re building something on Substack, build it fast. Monetize it. Own your audience. Move them to an independent mailing list. Stack your earnings like your life depends on it.

Because the sun is shining today. But one day, the storm will roll in. And by then, you’ll want to have already packed your bags.

In short, stack like there is no tomorrow. Because, guess what, there isn’t.

It's funny, your article was specifically about Substack but it applies so well to capitalism writ large. It really isn't the pursuit of profit that makes it so bad (most of the time), its the pursuit of profit GROWTH that causes the biggest problems.

Thanks for the wonderful writing.

it’s not just social media. Etsy was once a haven for creative folks (and a handful of pretentious assholes) that had discourse about whether a beaded item was “actually handmade”.

now they mostly feature dropship garbage from china and there isn’t even a feature to choose “only handmade” in the search any more.